|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| .. | ||

| apps | ||

| examples | ||

| 000organization.cc | ||

| 001help.cc | ||

| 002test.cc | ||

| 003trace.cc | ||

| 003trace.test.cc | ||

| 010---vm.cc | ||

| 011run.cc | ||

| 012elf.cc | ||

| 013direct_addressing.cc | ||

| 014indirect_addressing.cc | ||

| 015immediate_addressing.cc | ||

| 016index_addressing.cc | ||

| 017jump_disp8.cc | ||

| 018jump_disp32.cc | ||

| 019functions.cc | ||

| 020syscalls.cc | ||

| 021byte_addressing.cc | ||

| 028translate.cc | ||

| 029transforms.cc | ||

| 030---operands.cc | ||

| 031check_operands.cc | ||

| 032check_operand_bounds.cc | ||

| 034compute_segment_address.cc | ||

| 035labels.cc | ||

| 036global_variables.cc | ||

| 038---literal_strings.cc | ||

| 039debug.cc | ||

| 040---tests.cc | ||

| 050_write.subx | ||

| 051test.subx | ||

| 052kernel_string_equal.subx | ||

| 053new_segment.subx | ||

| 054string_equal.subx | ||

| 055trace.subx | ||

| 056write.subx | ||

| 057stop.subx | ||

| 058read.subx | ||

| 059read-byte.subx | ||

| 060write-stream.subx | ||

| 100index | ||

| Readme.md | ||

| build | ||

| build_and_test_until | ||

| c | ||

| cb | ||

| cheatsheet.pdf | ||

| clean | ||

| cr | ||

| dcr | ||

| dgen | ||

| drun | ||

| edit | ||

| gen | ||

| modrm.pdf | ||

| opcodes | ||

| run | ||

| sib.pdf | ||

| subx | ||

| subx.vim | ||

| test_apps | ||

| test_layers | ||

| vimrc.vim | ||

Readme.md

SubX: a simplistic assembly language

SubX is a minimalist assembly language designed:

- to explore ways to turn arbitrary manual tests into reproducible automated tests,

- to be easy to implement in itself, and

- to help learn and teach the x86 instruction set.

$ git clone https://github.com/akkartik/mu

$ cd mu/subx

$ ./subx # print out a help message

Expanding on the first bullet, it hopes to support more comprehensive tests by:

-

Running generated binaries in emulated mode. It's slower than native execution (which will also work), but there's more sanity checking, and more descriptive error messages for common low-level problems.

$ ./subx translate examples/ex1.subx -o examples/ex1 $ ./examples/ex1 # only on Linux $ echo $? 42 $ ./subx run examples/ex1 # on Linux or BSD or OS X $ echo $? 42The assembly syntax is designed so the assembler (

subx translate) has very little to do, making it feasible to reimplement in itself. Programmers have to explicitly specify all opcodes and operands.# exit(42) bb/copy-to-EBX 0x2a/imm32 # 42 in hex b8/copy-to-EAX 1/imm32/exit cd/syscall 0x80/imm8To keep code readable you can add metadata to any word after a

/. Metadata can be just comments for readers, and they'll be ignored. They can also trigger checks. Here, tagging operands with theimm32type allows SubX to check that instructions have precisely the operand types they should. x86 instructions have 14 types of operands, and missing one causes all future instructions to go off the rails, interpreting operands as opcodes and vice versa. So this is a useful check. -

Designing testable wrappers for operating system interfaces. For example, it can

read()from orwrite()to fake in-memory files in tests. We'll gradually port ideas for other syscalls from the old Mu VM in the parent directory. -

Supporting a special trace stream in addition to the default

stdin,stdoutandstderrstreams. The trace stream is designed for programs to emit structured facts they deduce about their domain as they execute. Tests can then check the set of facts deduced in addition to the results of the function under test. This form of automated whitebox testing permits writing tests for performance, fault tolerance, deadlock-freedom, memory usage, etc. For example, if a sort function traces each swap, a performance test could check that the number of swaps doesn't quadruple when the size of the input doubles.

The hypothesis is that designing the entire system to be testable from day 1 and from the ground up would radically impact the culture of an eco-system in a way that no bolted-on tool or service at higher levels can replicate. It would make it easier to write programs that can be easily understood by newcomers. It would reassure authors that an app is free from regression if all automated tests pass. It would make the stack easy to rewrite and simplify by dropping features, without fear that a subset of targeted apps might break. As a result people might fork projects more easily, and also exchange code between disparate forks more easily (copy the tests over, then try copying code over and making tests pass, rewriting and polishing where necessary). The community would have in effect a diversified portfolio of forks, a “wavefront” of possible combinations of features and alternative implementations of features instead of the single trunk with monotonically growing complexity that we get today. Application writers who wrote thorough tests for their apps (something they just can’t do today) would be able to bounce around between forks more easily without getting locked in to a single one as currently happens.

However, that vision is far away, and SubX is just a first, hesitant step. SubX supports a small, regular subset of the 32-bit x86 instruction set. (Think of the name as short for "sub-x86".)

-

Only instructions that operate on the 32-bit integer E*X registers, and a couple of instructions for operating on 8-bit values. No floating-point yet. Most legacy registers will never be supported.

-

Only instructions that assume a flat address space; legacy instructions that use segment registers will never be supported.

-

No instructions that check the carry or parity flags; arithmetic operations always operate on signed integers (while bitwise operations always operate on unsigned integers).

-

Only relative jump instructions (with 8-bit or 32-bit offsets).

The (rudimentary, statically linked) ELF binaries SubX generates can be run natively on Linux, and they require only the Linux kernel.

Status: SubX is currently implemented in C++, so you need a C++ compiler and

libraries to build SubX binaries. However, I'm learning how to build a

compiler in assembly language by working through Jack Crenshaw's "Let's build

a compiler" series. Look in the apps/

sub-directory.

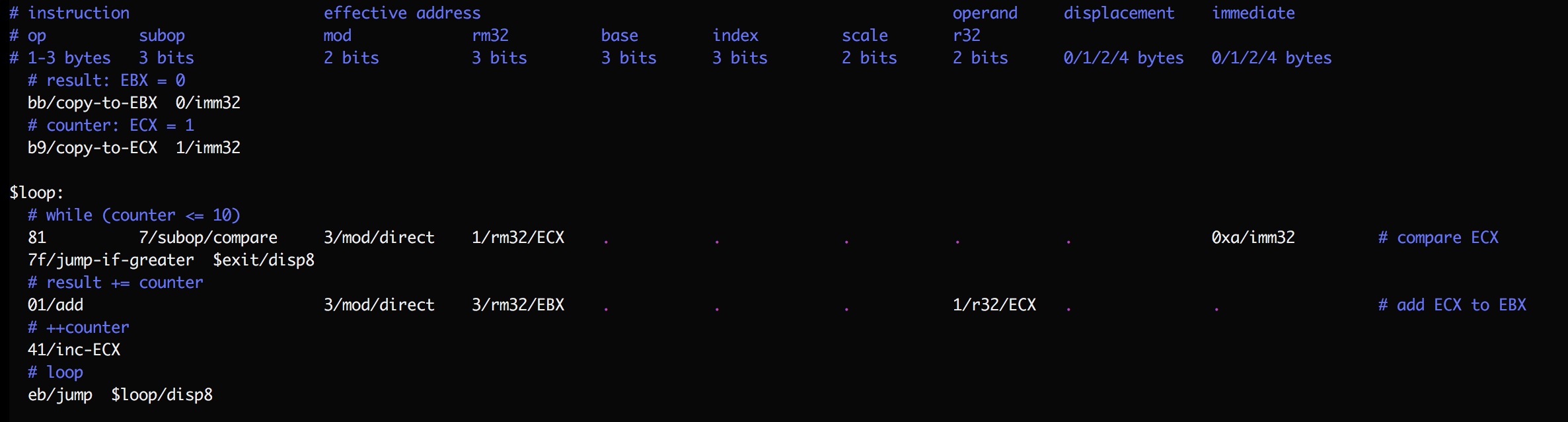

An example program

In the interest of minimalism, SubX requires more knowledge than traditional assembly languages of the x86 instructions it supports. Here's an example SubX program, using one line per instruction:

This program sums the first 10 natural numbers. By convention I use horizontal tabstops to help read instructions, dots to help follow the long lines, comments before groups of instructions to describe their high-level purpose, and comments at the end of complex instructions to state the low-level operation they perform. Numbers are always shown in hexadecimal (base 16).

As you can see, programming in SubX requires the programmer to know the (kinda

complex) structure of x86 instructions, all the different operands that an

instruction can have, their layout in bytes (for example, the subop and

r32 fields use the same bits, so an instruction can't have both; more on

this below), the opcodes for supported instructions, and so on.

While SubX syntax is fairly dumb, the error-checking is relatively smart. I try to provide clear error messages on instructions missing operands or having unexpected operands. Either case would otherwise cause instruction boundaries to diverge from what you expect, and potentially lead to errors far away. It's useful to catch such errors early.

Try running this example now:

$ ./subx translate examples/ex3.subx -o examples/ex3

$ ./subx run examples/ex3

$ echo $?

55

If you're on Linux you can also run it natively:

$ ./examples/ex3

$ echo $?

55

The rest of this Readme elaborates on the syntax for SubX programs, starting with a few prerequisites about the x86 instruction set.

A quick tour of the x86 instruction set

The Intel processor manual is the final source of truth on the x86 instruction set, but it can be forbidding to make sense of, so here's a quick orientation. You will need familiarity with binary and hexadecimal encodings (starting with '0x') for numbers, and maybe a few other things. Email me any time if something isn't clear. I love explaining this stuff for as long as it takes.

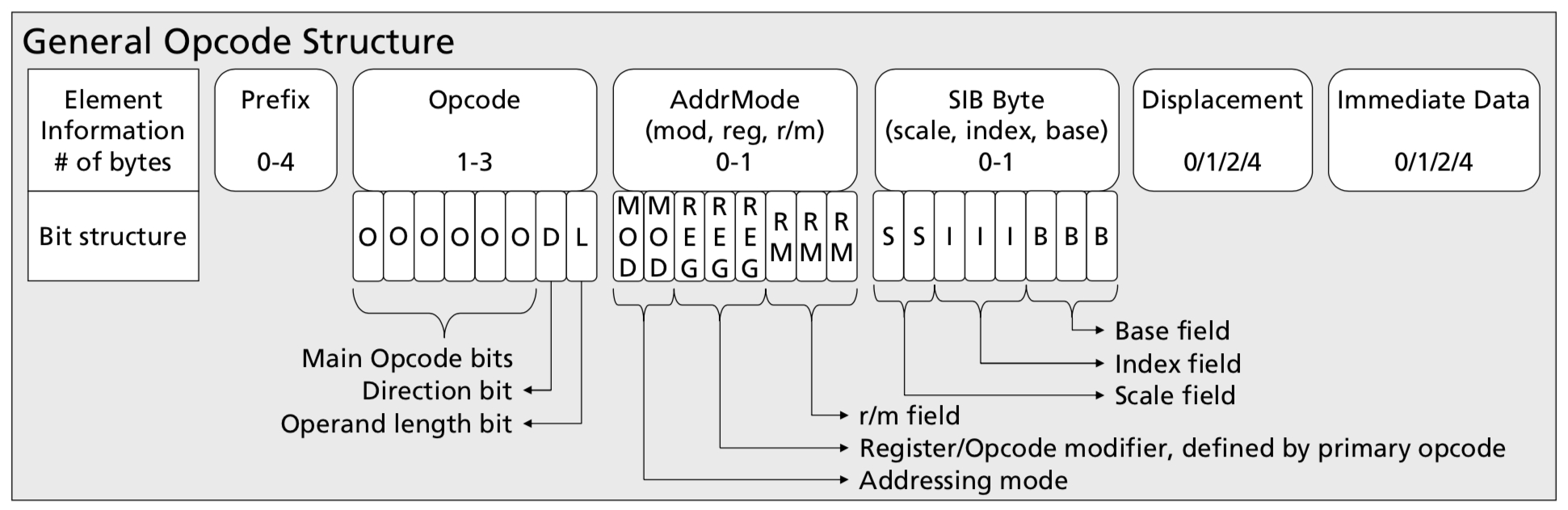

The x86 instructions SubX supports can take anywhere from 1 to 13 bytes. Early bytes affect what later bytes mean and where an instruction ends. Here's the big picture of a single x86 instruction from the Intel manual:

There's a lot here, so let's unpack it piece by piece:

-

The prefix bytes are not used by SubX, so ignore them.

-

The opcode bytes encode the instruction used. Ignore their internal structure; we'll just treat them as a sequence of whole bytes. The opcode sequences SubX recognizes are enumerated by running

subx help opcodes. For more details on a specific opcode, consult html guides like https://c9x.me/x86 or the Intel manual. -

The addressing mode byte is used by all instructions that take an

rm32operand according tosubx help opcodes. (That's most instructions.) Therm32operand expresses how an instruction should load one 32-bit operand from either a register or memory. It is configured by the addressing mode byte and, optionally, the SIB (scale, index, base) byte as follows:-

if the

mod(mode) field is 3: therm32operand is the contents of the register described by ther/mbits.000(0) means registerEAX001(1) means registerECX010(2) means registerEDX011(3) means registerEBX100(4) means registerESP101(5) means registerEBP110(6) means registerESI111(7) means registerEDI

-

if

modis 0:rm32is the contents of the address provided in the register provided byr/m. That's*r/min C syntax. -

if

modis 1:rm32is the contents of the address provided by adding the register inr/mwith the (1-byte) displacement. That's*(r/m + disp8)in C syntax. -

if

modis 2:rm32is the contents of the address provided by adding the register inr/mwith the (4-byte) displacement. That's*(r/m + disp32)in C syntax.

In the last 3 cases, one exception occurs when the

r/mfield contains010or 4. Rather than encoding register ESP, '4' means the address is provided by a SIB byte next:base * 2^scale + index(There are a couple more exceptions ☹; see Table 2-2 and Table 2-3 of the Intel manual for the complete story.)

Phew, that was a lot to take in. Some examples to work through as you reread and digest it:

-

To read directly from the EAX register,

modmust be11or 3 (direct mode), and ther/mbits must be000(EAX). There must be no SIB byte. -

To read from

*EAXin C syntax,modmust be00(indirect mode), and ther/mbits must be00. There must be no SIB byte. -

To read from

*(EAX+4),modmust be01or 1 (indirect + disp8 mode),r/mmust be000, there must be no SIB byte, and there must be a single displacement byte containing00000010or 4. -

To read from

*(EAX+ECX+4), one approach would be to setmodto01,r/mto100(SIB byte next),baseto000,indexto001(ECX) and a single displacement byte to 4. What should thescalebits be? Can you think of another approach? -

To read from

*(EAX+ECX+0x00f00000), one approach would be:mod:10(indirect + disp32)r/m:100(SIB byte)base:000(EAX)index:001(ECX)displacement: 4 bytes containing 0x00f00000

-

-

Back to the instruction picture. We've already covered the SIB byte and most of the addressing mode byte. Instructions can also provide a second operand as either a displacement or immediate value (the two are distinct because some instructions use a displacement as part of

rm32and an immediate for the other operand). -

Finally, the

regbits in the addressing mode byte can also encode the second operand. Sometimes they can also be part of the opcode bits. For example, an operand byte offfandregbits of001means "increment rm32". (Notice that instructions that use theregbits as a "sub-opcode" cannot also use it as a second operand.)

That concludes our quick tour. By this point it's probably clear to you that the x86 instruction set is overly complicated. Many simpler instruction sets exist. However, your computer right now likely runs x86 instructions and not them. Internalizing the last 750 words may allow you to program your computer fairly directly, with only minimal-going-on-zero reliance on a C compiler.

The syntax of SubX programs

SubX programs map to the same ELF binaries that a conventional Linux system

uses. Linux ELF binaries consist of a series of segments. In particular, they

distinguish between code and data. Correspondingly, SubX programs consist of a

series of segments, each starting with a header line: == followed by a name.

The first segment is assumed to be for code, and the second for data. By

convention, I name them code and data.

Execution always begins at the start of the code segment.

You can reuse segment names:

== code

...A...

== data

...B...

== code

...C...

The code segment now contains the instructions of A as well as C. C

comes before A. This order allows me to split SubX programs between

multiple layers. A program built with just layer 1 would start executing at

layer 1's first instruction, while one built with layer 1 and layer 2 (in that

order) would start executing at layer 2's first instruction.

Within the code segment, each line contains a comment, label or instruction.

Comments start with a # and are ignored. Labels should always be the first

word on a line, and they end with a :.

Instructions consist of a sequence of opcode bytes and their operands. As

mentioned above, each opcode and operand can contain metadata after a /.

Metadata can be either for SubX or act as a comment for the reader; SubX

silently ignores unrecognized metadata. A single word can contain multiple

pieces of metadata, each starting with a /.

SubX uses metadata to express instruction encoding and get decent error messages. You must tag each instruction operand with the appropriate operand type:

modrm32("r/m" in the x86 instruction diagram above, but we can't use/in metadata tags)r32("reg" in the x86 diagram)subop(for when "reg" in the x86 diagram encodes a sub-opcode rather than an operand)- displacement:

disp8,disp16ordisp32 - immediate:

imm8orimm32

You don't need to remember what order instruction operands are in,

or pack bitfields by hand. SubX will do all that for you. If you get the types

wrong, giving an instruction an incorrect operand or forgetting an operand,

you should get a clear error message. Remember, don't use subop (sub-operand

above) and r32 (reg in the x86 figure above) in a single instruction.

Instructions can refer to labels in displacement or immediate operands, and

they'll obtain a value based on the address of the label: immediate operands

will contain the address directly, while displacement operands will contain

the difference between the address and the address of the current instruction.

The latter is mostly useful for jump and call instructions.

Functions are defined using labels. By convention, labels internal to functions

(that must only be jumped to) start with a $. Any other labels must only be

called, never jumped to.

The data segment consists of labels as before and byte values. Referring to

data labels in either code segment instructions or data segment values (using

the imm32 metadata either way) yields their address.

Automatic tests are an important part of SubX, and there's a simple mechanism

to provide a test harness: all functions that start with test- are called in

turn by a special, auto-generated function called run-tests. How you choose

to call it is up to you.

I try to keep things simple so that there's less work to do when I eventually

implement SubX in SubX. But there is one convenience: instructions can

provide a string literal surrounded by quotes (") in an imm32 operand.

SubX will transparently copy it to the data segment and replace it with its

address. Strings are the only place where a SubX operand is allowed to contain

spaces.

That should be enough information for writing SubX programs. The examples/

directory provides some fodder for practice, giving a more gradual introduction

to SubX features. This repo includes the binary for all examples. At any

commit, an example's binary should be identical bit for bit with the result of

translating the corresponding .subx file. The binary should also be natively

runnable on a Linux system running on Intel x86 processors, either 32- or

64-bit. If either of these invariants is broken it's a bug on my part.

Running

Running subx will transparently compile it as necessary.

subx currently has the following sub-commands:

-

subx help: some helpful documentation to have at your fingertips. -

subx test: runs all automated tests. -

subx translate <input files> -o <output ELF binary>: translates.subxfiles into an executable ELF binary. -

subx run <ELF binary>: simulates running the ELF binaries emitted bysubx translate. Useful for debugging, and also enables more thorough testing oftranslate.Remember, not all 32-bit Linux binaries are guaranteed to run. I'm not building general infrastructure here for all of the x86 instruction set. SubX is about programming with a small, regular subset of 32-bit x86.

SubX library

A major goal of SubX is testable wrappers for operating system syscalls. Here's what I've built so far:

-

write: takes two arguments,fands.sis an address to an array. Arrays in SubX are always assumed to start with a 4-byte length.fis either a file descriptor to writesto, or (in tests) a stream. Streams are in-memory buffers that can be read or written. They consist of adataarray of bytes as well asreadandwriteindexes into the array, showing how far we've read and written so far.

Comparing this interface with the Unix

write()syscall shows two benefits:-

SubX can handle 'fake' file descriptors in tests.

-

write()accepts buffer and its length in separate arguments, which requires callers to manage the two separately and so can be error-prone. SubX's wrapper keeps the two together to increase the chances that we never accidentally go out of array bounds.

-

read: takes two arguments,fands.fis either a file descriptor to read from, or (in tests) a stream.sis an address to a stream to save the read data to. We read as much data as can fit in (the free space of)s, and no more.

Like with

write(), this wrapper around the Unixread()syscall adds the ability to handle 'fake' file descriptors in tests, and reduces the chances of clobbering outside array bounds.One bit of weirdness here: in tests we do a redundant copy from one stream to another. See the comments before the implementation for a discussion of alternative interfaces.

-

stop: takes two arguments:edis an address to an exit descriptor. Exit descriptors allow us toexit()the program in production, but return to the test harness within tests. That allows tests to make assertions about whenexit()is called.valueis the status code toexit()with.

For more details on exit descriptors and how to create one, see the comments before the implementation.

-

... (to be continued)

Resources

- Single-page cheatsheet for the x86 ISA (pdf; cached local copy)

- Concise reference for the x86 ISA

- Intel processor manual (pdf)

Inspirations

- “Creating tiny ELF executables”

- “Bootstrapping a compiler from nothing”

- Forth implementations like StoneKnifeForth